A seat at the wrong table

| This article was originally published on SYRIA UNTOLD |

Last month, Syria was elected to the WHO’s Executive Board. The body chose a regime that succeeded in destroying a nation’s healthcare system, displacing its practitioners, weakening its capacity to respond and manipulating its resources until the system was decades behind in a matter of just a few years.

The World Health Organization announced late last month that Syria had been elected to its Executive Board. According to its website, Hassan Ghabash, Syria’s health minister since 2020 and former head of the Syrian Doctors Syndicate, will be representing the country. The internal regulations of the WHO allow Ghabash to appoint representatives and advisors to support him during his mission. It is important to note that Ghabash has been on the UK’s list of sanctioned individuals since March 2021 and on the EU’s list since 2020.

The Executive Board oversees implementation of the WHO’s policies and is responsible for following up on the execution of the resolutions made by the World Health Assembly. This structure grants the Executive Board vast powers, as it is entrusted with implementing policies and has the power to respond to emergencies, create funds for those responses and decide on the budget that the Director-General will present to the World Health Assembly. Composed of representatives from 34 countries, the Executive Board also recommends a Director-General and decides on the time and location of sessions, among other duties. Nations represented on the board are distributed in a way that guarantees regional balance among the 194 UN member states. Each of them has a three-year term on the board.

The Syrian government’s deep history of corruption

The Syrian state has a long history of corruption, exploiting UN agencies and politicizing aid. This all begins with the needs assessments, the planning, the allocation of funds, the hiring of sub-contractors and staff, procurement and implementation. The corruption and exploitation extend to the processes of oversight and evaluation.

Damascus has repeatedly used UN agencies to bypass sanctions imposed by the US and EU on Syrian figures close to the regime. Contracts are drafted to benefit those close to the regime. For example, the value of contracts between the UN and Syriatel, a telecommunications company owned by Bashar al-Assad’s cousin Rami Makhlouf, amounts to $700,000. UN agencies have spent more than $12 million between 2014 and 2015 alone at the Four Seasons, a hotel in Damascus. In fact, the Syrian Ministry of Tourism owns a third of shares at the Four Seasons. Added to that are the dozens of contracts to fund organizations that hide behind a facade humanitarianism, like Makhlouf’s Al Bustan Association and Asma al-Assad’s Syria Trust for Development.

The Syrian state has a long history of corruption, exploiting UN agencies and politicizing aid.

UN agencies and Syrian government ministries have been heavily criticized for interfering in employment processes. In 2016, the WHO faced condemnation for hiring Shukria Mekdad, the wife of Syrian deputy foreign minister Faisal Mekdad. He had been negotiating with the UN to pass the yearly humanitarian response plan for Syria.

In 2013, the Syrian government launched the High Relief Committee, which included the ministers of labor, social affairs and health. Ghabash, the minister of health, is now on the WHO’s Executive Board, officially representing Syria. The Committee has been involved in designing and implementing humanitarian programs, including the delivery of humanitarian aid convoys.

It is important to note that only 10 percent of aid in Syria was delivered in 2015, while the Syrian government ignored 75 percent of requests and rejected 15 percent. The remaining 10 percent that actually made it through was not spared the regime’s meddling. Aid supplies were repeatedly removed from packages, while other items reached some areas after expiry and some packages reached the wrong areas altogether. The Syrian government’s meddling starts at the office of the foreign affairs minister and ends with the most junior security officer sitting at the checkpoints that the supplies must traverse.

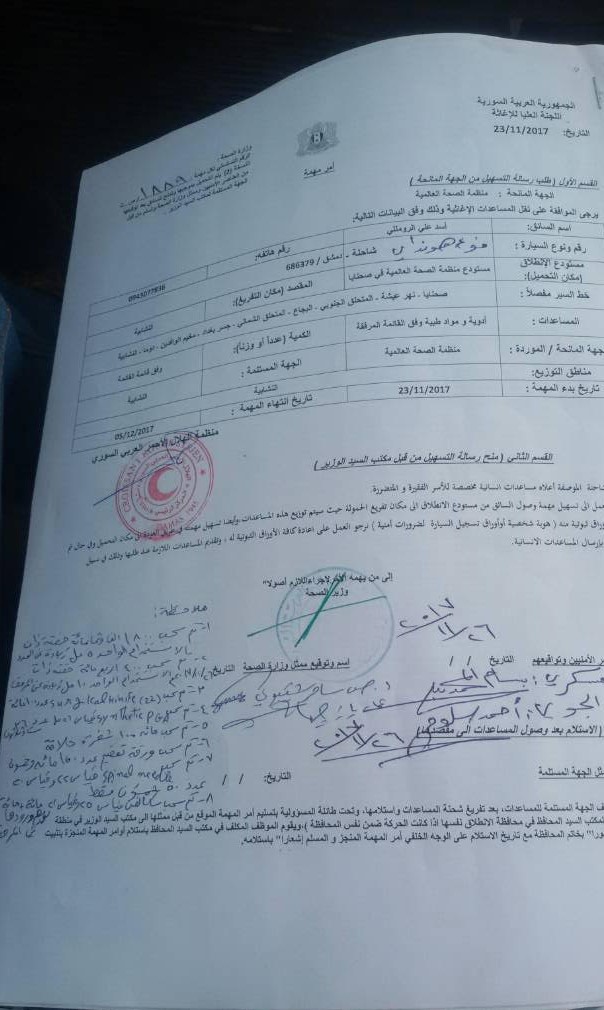

The document shown above is from the end of 2017. It shows a request submitted to the High Relief Committee to facilitate the movement of a truck carrying aid funded by the WHO. The document is signed and sealed by the health minister and the Red Crescent. The supplies are set to be delivered to a military official who would then remove some products from the truck despite the fact that the health minister has agreed to the delivery. It appeared that all the supplies removed were medical products that cannot be used to manufacture anything dangerous.

In the third month of 2018, a convoy delivering aid reached East Ghouta, at the time under a punishing siege and bombardment campaign by regime forces. After workers unloaded the vehicles, an officer representing the Russian military called and ordered them to leave within a few hours. And this is what happened. Although led by Ali al-Zaatari, the UN’s humanitarian coordinator in Syria—the highest UN official in the country—the convoy left before unloading all nine trucks.

There are dozens of examples of corruption and politicization of UN aid in Syria. I remember an interview with a health response worker in Damascus. He mentioned that the funding allocated by the WHO was intended to restore the health facilities destroyed by shelling. The allocation of funds was based on an assessment that included several areas reclaimed by the regime such as eastern Aleppo and East Ghouta, but the government approvals for implementation never arrived in time, before the expiry of the funding agreements. The WHO also followed the instructions of the Syrian Ministry of Health, which redirected support to hospitals in Homs and Hama, areas that were the backbone of the regime’s attack on rebel-held Idlib in 2019. The funding even reached a medical facility on the Syrian-Lebanese border that was used for triage before moving injured Hezbollah fighters to Lebanon. Additionally, the WHO gave more than $5 million to a blood bank affiliated with the Ministry of Defense, not the Ministry of Health.

Crimes against the right to health

In terms of criminal liability, the Syrian government along with its Russian ally are responsible for more than 90 percent of strikes targeting healthcare facilities in Syria, with approximately 599 strikes. The most recent attack, in late March, struck Al-Atareb Surgical Hospital in the countryside of western Aleppo. Over the course of a decade, more than 930 people working in healthcare have been killed in Syria, including 185 who died of torture in Syrian regime prisons.

Aid organizations have tried pressuring the Syrian regime and its allies to reduce strikes on hospitals. There have been numerous reports issued about such strikes and the ways healthcare workers have protected their facilities, such as building underground structures and alarm systems to warn against air raids. They even tried protecting themselves from air raids by sharing their coordinates as part of the UN’s “humanitarian deconfliction mechanism”, which was shared with warring parties. However, the Syrian regime continued developing its killing machine, including targeting medical facilities. Regime forces even repeatedly used chemical weapons when bombing hospitals. I remember the images of Dr. Ali Darwish, who was killed in 2017 when regime forces fired chlorine-laden bombs on his hospital in rural Hama.

On top of all this, the Syrian regime weaponized humanitarian aid during the war, using its influence and power to block aid from reaching specific areas and redirect it to others. Hundreds died when some opposition-held areas were denied humanitarian aid. In the town of Madaya alone, it took only six months of siege to kill 86 people.

The Syrian government’s meddling starts at the office of the foreign affairs minister and ends with the most junior security officer sitting at the checkpoints that the supplies must traverse.

Syrian government policies draining and politicizing the healthcare system

The healthcare system in Syria was overwhelmed with corruption even before 2011, though the human resources and local medications managed to compensate and cover 95 percent of needs. Yet more than 70 percent of those medical professions have left Syria. The average work hours for healthcare practitioners reached 80 hours per week, especially for rare specializations. There is one doctor for every 10,000 people, and the average life expectancy in Syria has dropped from 70 years in 2010 to 55 years today.

The availability of medication in pharmacies also dropped sharply, as drug companies function at 5 percent capacity. Only 64 percent of Syrian hospitals and 52 percent of primary healthcare centers are functional. The rest have been suspended, either because they were destroyed or because they no longer have any funding. In many areas, like East Ghouta and eastern Aleppo, once the regime reclaimed control from rebels, it blocked aid organizations from entry and did not provide public services. More than years after the regime reclaimed the city of Douma in East Ghouta, the area remains without access to public healthcare.

The Syrian Ministry of Health also privatized the major hospitals, which since 2012 have charged fees for healthcare. This left the capital, Damascus, and its approximately 4 million residents with just one public hospital, the Ibn Al Nafees Hospital.

Covid-19 response

In the beginning of 2021, the Syrian Doctors Syndicate declared that 130 doctors had died of COVID-19. However, a number of reports have shown that the Syrian regime used COVID-19 as a way to cover up the murders of doctors under torture. This number is very concerning and reveals the lack of protection towards medical practitioners in Syria.

It is also possible for Syrians to pay a few hundred dollars to obtain a negative Covid-19 test, in order to travel or arrange paperwork that requires a negative test result. The Syrian government meddled with the case numbers in Syria, left its people to face the pandemic alone and denied the magnitude of the disaster. Damascus dealt with the pandemic as if it were a security issue, adopting the same old strategies it uses to resolve all other issues.

Over the course of a decade, the Syrian government proved that it is capable of exploiting anything and everything. Humanitarian aid, the lives of healthcare workers, the health of the Syrian people, the country’s healthcare system, infrastructure and logistics are all first and foremost tools for the regime to achieve military and political victory. They are also tools to benefit the mafia tightly linked to the head of the regime, Assad, and his family.

The WHO has allowed the current Syrian health minister to occupy a seat on its executive board. It has therefore not expressed any resistance to the corruption, the politicization and the militarization of aid. By doing so, the WHO is providing a model for other countries that want to intervene in aid. Instead of sanctioning such behavior with the simplest of instruments—boycott—the organization grants them a seat among decision-makers.

The World Health Assembly not only chose a criminal government, but they also chose a regime that succeeded in destroying a nation’s health system, displacing its practitioners, weakening its capacity to respond and manipulating its resources until the system was decades behind in a matter of just a few years. This same regime is now in a leadership position at the WHO, which is responsible for global health policies.

Mohamad Katoub is a Syrian dentist and human rights activist. For the past decade, he has worked on humanitarian response and monitoring violations against healthcare workers and medical access.